“Obstinately, Chicago refuses to let in the spring…. Most students are staying inside, reading their books, keeping dry. But 20 are out on the wet lawn of the quadrangle in small tents, not eating anything, waiting for the administration to change its mind.”

This 1969 description of a quad covered in tents and an administration estranged from its students is strikingly reminiscent of the current encampment on the quad, which began in the early hours of Monday, April 29, to protest the war in Gaza and demand the University’s “full divestment from companies complicit in the ongoing occupation and genocide in Palestine.”

Before their “tent-in,” the 1969 student demonstrators occupied the University’s Administration Building to protest, among other things, the inauguration of President Edward Levi. The Administration Building—now known as Edward H. Levi Hall and emblazoned just two nights ago with projections of “From the river to the sea,” “By any means necessary,” “Free Palestine,” and “Fuck Paul”—bears the marks of an ongoing conflict between administration and students.

The pro-Palestine encampment is but the latest—and largest—iteration in a tradition of occupations, sit-ins, and tent-ins at the University of Chicago.

The Maroon’s deep dive into digital archives presents a lineage of civil disobedience and radical action by students against the administration over collegiate, local, and international issues. Grey City has compiled some of the more notable examples here.

1962: Students sit-in against segregated university-owned housing

The first sit-in at the University took place in 1962, when the Maroon revealed that the University would not rent off-campus properties to Black tenants in Hyde Park.

Undergraduate members of the UChicago chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), confronted the University’s president, George Beadle. But Beadle’s administration showed reluctance.

Nina Helstein (Ph.D. ’95), a second-year in the College at the time and a member of CORE, recalled a letter from the President to the group that said, essentially, “We agree with you, we think what you’re saying is totally right, but this isn’t the time.”

She and 30 of her classmates were led by Bruce Rappaport (A.B. ’64) and Bernie Sanders (A.B. ’64), student leaders of CORE, into the President’s office in the Administration Building. “We feel it is an intolerable situation when Negro and white students of the University cannot live together in University-owned apartments,” Sanders said at the time.

“We were sitting all night on the floor,” Helstein recalled of the sit-in. “It was very, very boring, and I personally got sick of all the pizza boxes on the floor.”

“It’s not fun doing those things,” she said of her years of civil disobedience. “But I think it made a difference actually.”

In a 2015 interview with UChicago Magazine, Sanders only breathed a “weary sigh” when reminded that his 1962 sit-in ended with a compromise: “the formation of a committee of faculty, students, and representatives of civic and community groups to discuss and investigate the matter.”

But his moral resolve and support for campus protests remain the same. Just this Friday—as counterprotesters in cigar smoke and black cowboy hats clashed with the pro-Palestine encampment—Sanders wrote on X that “we were right.”

“I’m proud to see students protesting the war in Gaza,” he said. “Stay peaceful and focused. You’re on the right side of history.”

1966: Occupation against Selective Service

As the 1960s wore on, the rift between administrations and student bodies was pulled even wider by events both international and hyperlocal.

In May 1966, students occupied the Administration Building again for a week to protest “university co-operation with the selective service system,” which has maintained data about U.S. citizens in case of a draft since 1917.

The administration took issue mostly with the tactics of the protestors. “You can march around the building, carrying picket signs. You can sit in front of the building—we’ll even provide tables and lounge chairs. But just move out of the building,” urged Wayne Booth, then dean of the college.

Some demonstrators remained in the building for seven days, although most of the 450 initial students had dispersed before the weekend. On the final day, the remaining students left the Administration Building voluntarily to deliver a statement to the president’s house on University Avenue along with a glut of other protestors.

“Carrying sleeping bags, blankets, pillows, and books they turned south on University Avenue. A feeling of emotional elation pervaded the 400 marching demonstrators. Many of them had been in the ad building [for] more than fifty four straight hours, and now it was over,” the Maroon reported on May 17, 1966.

1968: On-campus housing shortages spur tent encampment on quad

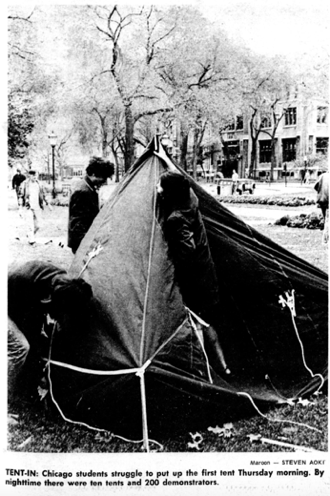

The war in Vietnam continued to put stress on the administration’s relationship with its students as the University had to reconcile international pressure and federal obligations with undergraduate discontent. At the beginning of the 1968–69 academic year, students faced an on-campus housing shortage at UChicago. Over the summer, the administration predicted that a significant number of students would be drafted for the war, which would open up housing space. The University’s expectations, however, were inaccurate, leaving it scrambling to find housing for a surplus of students, including “placing bunk beds in single rooms to house freshmen and arranging with local hotels to provide University-subsidized housing for other students.”

To protest the University’s housing mismanagement and cold calculations against its undergraduates, 200 students staged a “tent-in” on the main quad in mid-October. “Many students were charging that the administration was not dealing realistically with the combined effect of increased enrollment and loss of housing units to urban renewal,” a Maroon article from 15 years later reflected.

The students claimed that the tent-in was distinct from a sit-in. “It should be really clear that it’s not a confrontation,” said one student at a planning meeting for the tent-in. It was instead a way of making the housing crisis in Hyde Park exceedingly and dramatically visible. As another student put it at the time, referring to the administration,“they have turned Hyde Park into an upper-middle-class neighborhood. The irony is that this is no longer even a place for students.”

A week after the tent-in began, a 170-page, University-funded report concluded that it “must either provide additional housing, or realistically reduce further growth.” Soon enough, however, new issues to protest surpassed housing concerns.

1968: Black student inequality triggers short-lived occupation and scoff from admin

In May of the same year, a group of 40 Black students occupied the Administration Building for just four hours, before marching out of their own volition. According to a Maroon article, the Black Student Alliance (BSA) demanded, among other things, “an eleven percent black quota in the College” and the “conversion of Boucher Hall into a coed black dormitory.”

(The Maroon Archives)

The University called the BSA’s efforts “disruptive,” and Dean of Students Charles O’Connell dismissed the students’ demands, noting that “next year’s freshman class would have more black students than any other class in the University’s history.” (As of 2022, the University’s Black population was only 6 percent.)

1969: A two-week occupation of Administration Building brings 37 expulsions

During the inauguration of University President Edward Levi in November 1968, sociology professor Marlene Dixon stepped out of the procession of faculty to join a group of students protesting the Vietnam War and Levi’s appointment. “Dixon’s action was considered insignificant until it was discovered in early January 1969 that she would not be offered a three-year reappointment by the University, despite a unanimous decision by the faculty on the Committee for Human Development to recommend her for reappointment,” the Maroon later wrote.

An issue of the paper from January 7 correctly predicted that “the campus left will suspect underlying political motives.” The discontent manifested first with picket lines, protests, and ineffectual meetings with administrators. Then, students broke into the office of the dean of the social sciences, who, upon returning, “found that students were occupying it, that although he was permitted to sit in his chair he did not have access to the telephone, and that one student was engaged in looking through his files,” according to official University documents.

The same document noted that over 800 students massed in Kent Chemical Laboratory and voted to decide that a sit-in was a necessary form of protest “against discrimination against women, political suppression, and the narrow academic standards of the U. of C., and as an educational experience to explore the nature of the University and the education we are receiving here.”

(40 years after the occupation began, Classics professor James Redfield, who was the associate dean of the College at the time of the sit-in, suggested a more diverse range of motivations, telling Grey City that the demonstrators included “people who are ideologically committed. There are angry people. And there are guys who are picking up chicks.”)

On January 30, between 400 and 500 students “marched into the Administration Building and claimed it as their own, and insisted that they would keep it forever or until Marlene Dixon was rehired,” an editorial by student radio station WHPK in the Maroon noted on the first anniversary of the occupation.

“The students had prepared for a lengthy stay,” the Maroon noted, “bringing large supplies of food into the building and dressing as casually and comfortably as they could. Many had written the names of two law students who were acting as legal liaisons on their hands with ballpoint pens. Student marshalls patrolled the floors.”

During the first week, demonstrators held teach-ins, the Maroon published special daily issues about the occupation, and the group, which had dwindled to about 150 students, voted to stay another week.

Levi, notably, refused to call the Chicago city police to evict his own students from the Administration Building. But the University took aggressive disciplinary action against its students once the two-week occupation had ended. 164 went before a disciplinary committee. 37 were expelled, and 62 were suspended for varying lengths of time.

Just one year after the chaos on campus, the WHPK editorial saw a general “retreat into apathy.” The revolutionary spirit, it seemed, was over.

“There has been a reaction against the unilateral theatrics which so shocked Middle America,” the editorial continued. “This is only natural and by itself might have led to a concern for more practical causes than simply disrupting the provincial lives of various universities.”

In the end, Dixon was never rehired, and the Administration Building is now called Edward H. Levi Hall.

1980s: Students politely and unsuccessfully demand divestment from South African Apartheid

In the 1980s, students at universities across the country protested against South Africa’s apartheid regime, pressuring their schools to divest. At UChicago, however, students made a conscious effort to keep the tension low and to adopt much milder tactics than those of the occupation of the Administration Building in the 1960s.

Sahotra Sarkar, Ph.D. ’89, a student leader of the divestment movement at UChicago in the late 1980s, told Grey City in 2015 that “after a lot of talking back and forth… it was decided that we did not want to commit civil disobedience because we did not want to divide the community.”

Peer institutions—like Columbia, Harvard, and the University of California system—divested after seeing greater disruption from students. In Berkeley’s case, there was “a level of activity the campus hadn’t seen since the ’60s disruption from student groups.”

At UChicago, as activists like Sakar intended, the community was not divided. Protests were tame, confined mostly to picket lines and letters to the Maroon from faculty and students alike. The University was not especially inconvenienced by these posters and letters and never fully divested from South African apartheid.

2011: Students and professors arrested at Occupy Chicago

In more recent years, student activism on campus has regained some of its bolder character and tactics.

2011 saw the Occupy Wall Street movement spread across the United States from the canyons of corporate skyscrapers in New York City. Thirteen students and faculty were arrested at Occupy Chicago in Grant Park, where protestors set up 500 tents and refused to leave at the park’s 11 p.m. closing time.

A sociology PhD student told the Maroon at the time that “the people who stayed in the encampment knew they were going to be arrested and were determined to follow through. That made the action particularly powerful.”

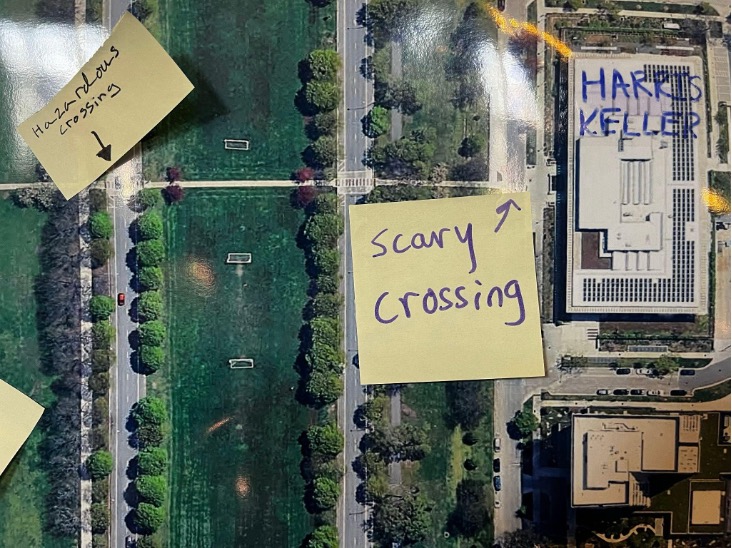

2020: #CareNotCops occupies the Provost’s block in Kenwood

In 2020, the student group #CareNotCops occupied the UCPD office for one night, as well as the block outside then provost Ka Yee Lee’s home in verdant Kenwood, to demand the abolition of UCPD and the creation of an ethnic studies department.

In a statement to the Maroon, #CareNotCops stated their demands for a public meeting with Lee, who controlled the budget in her capacity as provost. “The provost, her husband, and her neighbors are not innocent in the same way none of us are innocent,” the statement read. “Without action and intentionality, we are [complicit] in systemic harm.”

The #CareNotCops activists spent the week gathered around Lee’s home, holding rallies, delivering speeches, chanting, and shining lights into the house’s windows. The group also spray-painted vulgar messages in both English and Chinese characters on the sidewalk near Lee’s home, prompting accusations of anti-Asian racism and protest tactics that undermined the group’s original aim.

“We are there as part of the long lineage of students organizing alongside Southside communities in opposition to UChicago and its projects of extraction and displacement,” the #CareNotCops statement continued, situating itself in a lineage dating back to Bernie Sanders, his 32 undergraduate peers, and lots of empty pizza boxes sitting in the hallway of the Administration Building to protest housing segregation.

The #CareNotCops occupation ended with a block party outside Lee’s house, which fizzled as the police issued dispersal orders and the protestors marched to UCPD headquarters on 61st Street.

Still, as Lee told #CareNotCops, “the University has no intention of disbanding the UCPD.” The University’s police force appears poised, at some point or another, to take down the current pro-Palestine encampment on the quad as it enters its ninth day.

The tensions in this decades-long conflict between administration and students ebb and flow, and the causes change. But the methods of protest—and repression—remain more or less the same.

Lisa N. Knight (BS, MSc). Christian, alum, anti-DEI warrior / Sep 3, 2024 at 12:08 am

Civil rights riots. Call them what they were.

-Lisa

SR / May 11, 2024 at 4:47 pm

While this article focuses on the admin building, it would be great to add some of the other significant protest actions to this. Specifically, the trauma center campaign, the protests around the killing of Mike Brown in Ferguson, MO, and the protests against the Iraq war.

Steven Goldsmith / May 9, 2024 at 11:26 am

great story – current administration should hang their heads in shame